2025 Tariff War: Rebuilding International Trade Rules and Strategic Implications for Businesses

For companies engaged in global business operations, changes in the international trade regime have become an increasingly unavoidable management consideration. This article examines how current trade structures are evolving and explores the implications of these changes for corporate strategy and competitiveness.

The Current State of Global Trade Rules and Structures

The Multilateral Trade System Centered on the WTO

Since its establishment in 1995, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has been composed of 164 member countries and regions and has played a central role in promoting trade liberalization and stability. The WTO is built on several core principles that ensure non-discrimination, transparency, and predictability, thereby supporting the smooth functioning of international trade:

- Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) Treatment

Member countries are required to extend any trade advantages or privileges granted to one member unconditionally to all other members. - National Treatment

Imported goods must be treated no less favorably than domestically produced like products, prohibiting discriminatory practices. - Tariff Bindings

Members commit to upper limits on tariff rates, contributing to a predictable and stable trade environment.

The Rise of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

Multilateral negotiations under the WTO—most notably the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) launched in 2001—aimed to reduce agricultural subsidies, improve market access, and support developing countries. However, progress has stalled due to differences between developed and emerging economies, resulting in a diminished capacity to lead the formulation of new trade rules. As a result, countries have increasingly turned away from the WTO framework and accelerated the conclusion of regional trade agreements (RTAs) and free trade agreements (FTAs), which allow for the flexible establishment of high-standard rules covering tariff elimination, investment, e-commerce, and intellectual property protection. Representative agreements include the following:

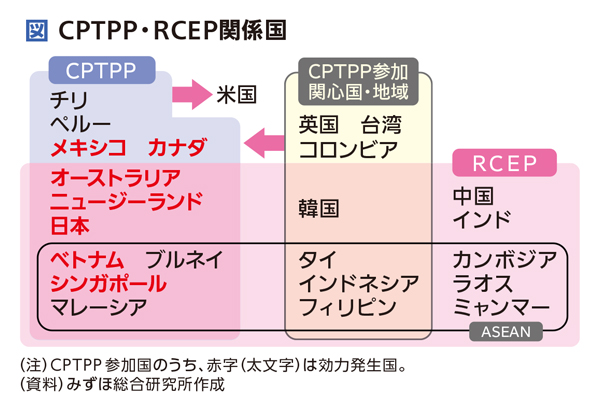

- Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

Originally conceived as the U.S.-led Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the agreement was restructured after the United States withdrew in 2017 and entered into force in 2018 under Japan’s leadership. It currently includes 11 participating countries, such as Japan, Canada, Mexico, Australia, and Vietnam. Beyond the phased elimination of tariffs, the CPTPP achieves a high level of liberalization across a wide range of areas, including intellectual property protection, disciplines on state-owned enterprises, and rules governing electronic commerce. - Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

Signed in 2020 and entering into force in 2022, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is the world’s largest free trade agreement, encompassing the 10 ASEAN member states as well as Japan, China, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The participating countries account for approximately 30% of global population, GDP, and trade, and the agreement is expected to promote economic integration across the Asia-Pacific region. In addition to tariff reduction, RCEP is characterized by the harmonization of rules of origin and the promotion of liberalization in services trade and investment.

Global Trade in 2025: Key Characteristics and Major Challenges

As of 2025, international trade is undergoing changes at an unprecedented pace, resulting in increasingly complex structures. The key characteristics of today’s global trade environment and the challenges associated with them can be summarized in the following four areas:

- Deepening and Restructuring of Global Value Chains (GVCs)

Global value chains (GVCs) refer to production systems in which goods are manufactured, assembled, and distributed through processes spanning multiple countries. In recent years, cross-border trade in intermediate goods and components has expanded, increasing economic interdependence among countries. In industries such as automotive, electronics, and pharmaceuticals, the efficiency of GVCs is a critical determinant of competitiveness. However, heightened geopolitical risks and supply chain disruptions triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic have prompted a shift in focus from “efficiency” to “resilience.” Both companies and governments are increasingly emphasizing risk management through supply chain diversification and regional dispersion. - Prolonged U.S.–China Tensions and Their Impact on the Trade Order

Trade friction between the United States and China, which intensified from 2018 onward, has expanded beyond tariff issues to encompass technological leadership, national security, and supply chain strategies. Export controls and investment restrictions targeting China in sectors such as semiconductors, AI, and 5G communications have had significant implications for global corporate strategies. As a result, many companies have adopted “China plus one” strategies, reducing reliance on China while accelerating investment in India and ASEAN countries. At the same time, the United States has strengthened trade and investment policies under the banner of “economic security,” in coordination with its allies. - The Rise of Emerging Economies and the Expansion of South–South Trade

In addition to China, emerging economies such as India, Indonesia, and Vietnam are playing increasingly prominent roles in global trade. Supported by abundant labor forces and the expansion of middle-income populations, these countries are growing both as manufacturing bases and as consumer markets. Of particular note is the increase in “South–South trade,” referring to trade among developing and emerging economies. Whereas trade traditionally centered on exchanges between developed and developing countries, direct trade among emerging economies has grown rapidly, heightening the importance of regional economic blocs. - Rapid Growth of Digital Trade and Lagging Rule-Making

“Digital trade,” encompassing e-commerce, cloud services, digital payments, and cross-border data flows, has emerged as a new pillar of global trade. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, both B2C and B2B electronic transactions have become firmly established, increasingly integrated with logistics and financial services. At the same time, international rule-making has lagged due to heightened concerns over data sovereignty and differences in privacy protection regimes across countries. Within the WTO, the Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on e-commerce is under discussion, but disagreements over issues such as data localization and algorithmic transparency remain significant obstacles.

U.S. Tariff Policy and Its Impact on Global Trade

In 2025, the Trump administration introduced a “reciprocal tariff” policy, imposing higher tariffs on a broad range of countries and regions with the aim of reducing the trade deficit and revitalizing domestic manufacturing. The impact of this policy extends beyond individual countries and affects the global trade environment as a whole:

- The Chain Reaction of Retaliatory Tariffs and a Shift Toward Regional Trade Agreements

In response to unilateral U.S. tariff measures, countries and regions such as China, the EU, and Canada have announced retaliatory tariffs. This situation has led to an environment in which power-based logic increasingly takes precedence over negotiations grounded in WTO rules. As a result, the framework for resolving trade disputes has weakened, and more countries are inclined to justify their own protectionist policies. - Reorganization of Global Value Chains (GVCs) and U.S. Economic Isolation

Japan’s automotive industry, in particular, has a high degree of export dependence on the United States, and increased tariff-related costs are putting pressure on profit margins. While local production expansion and the development of alternative markets—such as China and Southeast Asia—are accelerating, short-term disruptions to supply chains are anticipated. - Shifts Toward Emerging Economies and Inflationary Pressures

U.S. protectionist policies are accelerating trade shifts toward China, India, and Southeast Asia. At the same time, China faces concerns over domestic economic deceleration due to the combined impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing trade tensions with the United States.

Long-Term Outlook and the Search for a New Trade Order

The U.S. tariff war has provided other countries with a rationale to justify protectionist measures, accelerating the fragmentation of global trade. If countries continue to strengthen inward-looking policies, the efficiency of global value chains will decline.

Amid continued dysfunction within the WTO, countries are exploring the construction of new trade frameworks. For example, the EU and Japan are strengthening cooperation to uphold a rules-based trade system. In the Asia-Pacific region, regional trade agreements such as RCEP and CPTPP are attracting renewed attention, with efforts to advance trade liberalization and economic integration through these frameworks gaining momentum.

At the corporate level, efforts to diversify supply chains and distribute risk are also intensifying. Reducing dependence on specific countries or regions and building more flexible and sustainable supply systems will be a key strategic priority for global businesses going forward.

Summary

The institutional environment for international trade is gradually shifting from traditional multilateralism toward frameworks that emphasize regionalism and economic security. This structural transformation signifies not only heightened uncertainty for companies, but also the emergence of new growth opportunities. In an environment where countries adopt differing rules and standards, companies are required to demonstrate a high level of institutional understanding and strategic flexibility. Redefining corporate positioning and identifying new business opportunities will be essential to turning change from a risk into a source of competitive advantage.

Feel free to contact us

MAY Planning provides advisory services on regulatory compliance related to international trade, as well as risk assessment and optimization for supply chain restructuring. We also offer support in formulating strategies based on trade systems and policies in specific regions, particularly across ASEAN countries and Hong Kong.

References:

1)How to Prepare for Tariffs and the New Reality of Global Trade. (2025, February 13). BCG. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/prepare-tariffs-new-reality-global-trade

2)US Tariffs Set to Accelerate Landmark Shifts in Global Trade Flows. (2025, January 13). BCG. https://www.bcg.com/press/13january2025-landmark-shifts-global-trade-flows

3)Martin sandbu. (2025, May 8). Donald Trump’s Tariffs Will Boomerang on US Exporters. FINANCIAL TIMES. https://www.ft.com/content/a18ed1bd-3546-453a-bf11-72b5ac6a56f5

4)Kit norton. (2025, May 8). Trump Trade War: Shipping Giant Changes Outlook; Outlines Scenarios For U.S.-China Trade Talks. INVESTOR’S BUSINESS DAILY. https://www.investors.com/news/trump-trade-war-shipping-outlook-maersk-u-s-china-trade-talks/

5)Dispute Settlement in the World Trade Organization. (n.d.). WIKIPEDIA. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dispute_settlement_in_the_World_Trade_Organization

6)World Trade Organization. (n.d.). WIKIPEDIA. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_Trade_Organization

7)Doha Development Round. (n.d.). WIKIPEDIA. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doha_Development_Round

8)環太平洋パートナーシップ(TPP)協定交渉. (2025, February 7). 外務省. https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/tpp/index.html

9)Global Value and Supply Chains. (n.d.). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/global-value-and-supply-chains.html

10)経済安全保障政策. (n.d.). 経済産業省. https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/economy/economic_security/index.html

11)E-Commerce. (n.d.). World Trade Organization. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/ecom_e/ecom_e.htm